Millions of people live with mental health challenges, costing economies billions, while the window to avert the worst impacts of the environmental crises is closing. Engaging with nature offers a low-cost, scalable solution—boosting our wellbeing and inspiring us to act for the planet. But how do visiting nature and feeling connected to it work together to deliver these benefits? Our latest paper, published open access in People and Nature, explores this question, offering insights on how we can foster both human and environmental health.

Previous research has tended to focus on nature exposures, nature connection and key outcomes of wellbeing and environmentalism in isolation. Our latest work unites these aspects, supporting previous results found in isolation, but importantly demonstrating the compensatory and synergistic relationships at play. That is how exposure and connection can balance out weakness in the other, or how they can be combined for a greater effect.

We analysed data from the People and Nature Survey in England, involving thousands of participants (4,588–12,082), to understand how often people visit nature, how connected they feel to it, and how these factors relate to their wellbeing and environmental actions. We also considered the quality of nature in their neighbourhoods, so how good local green spaces are, and how this shapes the picture. Using advanced statistical models, we looked at how nature visits and connectedness interact to influence outcomes like mental wellbeing and nature conservation behaviours.

Something to sing about: Being both in and connected to nature unite human and nature’s wellbeing

Here’s the key aspects of what we found after accounting for the quality of people’s neighbourhood green and natural spaces or how good their passive nature exposure is. Importantly, both visiting nature and feeling connected to it were linked to better wellbeing and more environmental action. But the story gets more interesting when we look at how these two factors work together. For wellbeing, visiting nature more often brought bigger benefits for those who already felt highly connected to nature. However, for people with low connectedness, increasing their sense of connection made a bigger difference, especially if they rarely visited nature.

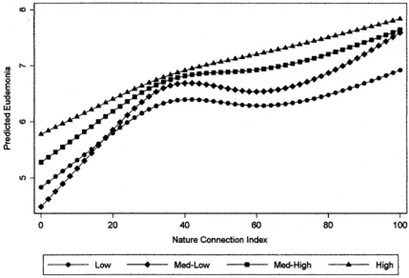

The chart below helps explain this. For the 12% of people with the lowest nature visits, the circular markers, the feeling that life is worthwhile increases rapidly as nature connection increases from 0 to 40—suggesting that even small steps to build connection can make a big difference. The findings suggest that a jump to very high nature visits may not contribute as much to wellbeing as connection does for this group. This trend levels off around the average level of mean NCI, 50. But as nature increases beyond 60, those with low nature visits reach average levels of feeling life is worthwhile, 6.8. This is when more visits could well deliver more benefit.

For the 44% of people with high visit frequency, the triangular markers, there’s a more consistent rise in wellbeing as nature connection increases. With wellbeing above average once nature connection is above average, hinting at a synergy where visits and connection amplify each other. The same broad trends are seen for happiness and life satisfaction – so both feeling good and functioning well.

The differences between the dotted lines show that more visits to nature can benefit mental wellbeing. With these benefits being greatest for those who feel the most emotional connection to nature. So, benefits are a product of nature exposure and connection working together. Interestingly, those with the highest level of visits and lowest connection aren’t as well as those with the highest connection and lowest level of visits.

Finally, for some people improving wellbeing through increased nature visit frequency might be difficult, for example disability may make nature visits impractical. For those in this position with very low nature connectedness (e.g., the bottom quartile of the population, where NCI scores are ≤ 31), useful forms of nature based social prescribing may focus on building connectedness in home-based settings, though for those with higher nature connectedness and negligible active nature exposure, increased connectedness may be of less value.

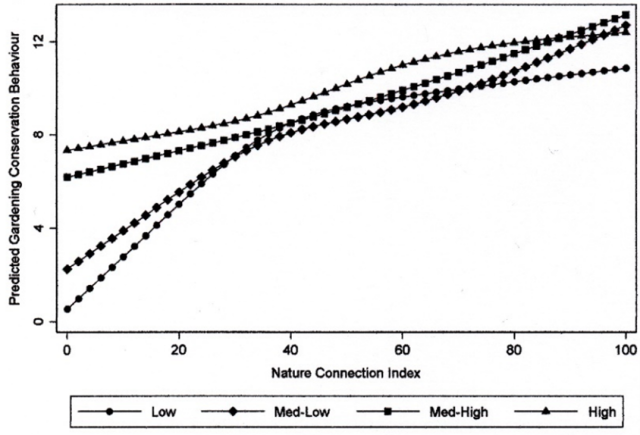

The environmental findings revealed some different dynamics, see the chart below. For people who don’t visit nature often, the circular markers, a stronger connection to nature significantly boosted their environmental actions, particularly at low connectedness levels—showing that building connection can inspire action even without frequent visits. Increased nature connection in the lowest 25% of nature visitors has clear effects. For those who visit nature more often, connection helps, but the effect is less dramatic. For more frequent visitors, a deepening their bond with nature can make a difference to pro-nature action.

The chart also highlights how from levels of nature connection just below the mean of 50, the level of visits makes less difference, as indicated by the lines being close together.

These patterns highlight the complexity of how nature visits and connectedness interact. Sometimes they compensate for each other—for example, lots more visits can make up for low connectedness in driving environmental action. Other times, they work synergistically, like when frequent visits and high connectedness together amplify wellbeing. Understanding these nuances can help us target interventions more effectively, ensuring we reach people where they are in their nature journey.

Implications

So, what does this mean for policy ideas like ‘Green in 15’ and practice? Although differential benefits are a challenge for policy making, the results demonstrate a straightforward principle: for maximum benefit to help unite both human and nature’s wellbeing there is a need to increase opportunities to access to high quality local nature and to build individual levels of nature connectedness.

For wellbeing, nature-based interventions like social prescribing should prioritise building connectedness, especially for those with low connection or limited access to nature. For environmental action, increasing nature visits can spark change for those with lower connectedness, while deepening connection can amplify conservation efforts among frequent visitors.

Increasing nature access and thereby visits is the most frequent objective to realise the wellbeing benefits of nature, with little consideration of the opportunity to deliver the co-benefit of environmental behaviour. However, our findings suggest that environmental benefits are more likely to come from strategies which increase nature connectedness than strategies which increase nature visits.

Focussing on access and visits to nature is more straightforward, but we know nature connection can be targeted and improved. Indeed, it is a powerful strategy for transformative change recommended by IPBES.

Key takeaways

Finding that those with the highest level of visits and lowest connection aren’t as well as those with the highest connection and lowest level of visits is a reminder to move beyond access only policy focus. Doing so will bring the maximum benefits for human health and environmental actions. So key takeaways are:

Foster Nature Connectedness

- Develop programs and campaigns using approaches like the pathways to nature connectedness that encourage interaction with nature to build meaningful and emotional connections to nature across education, health, and urban planning.

Target Interventions Based on Connection and Nature Visit Levels

- For individuals with low nature connectedness (bottom 25%), prioritise initiatives that build bonds with nature, as small increases in connectedness could well yield significant wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviour gains – plus are likely to motivate more visits creating a virtuous cycle.

- For those already connected but with low visit frequency, encourage more nature visits to amplify synergistic benefits for wellbeing.

- Incorporate Nature-Based Social Prescribing into healthcare systems, particularly for mental health.

- For individuals unable to visit nature frequently, prescribe home-based activities to boost connectedness.

Nature Rich Green Spaces

- Nature rich neighbourhood green spaces can encourage more visits and be designed to foster connectedness. Urban design can help by making nature visible and inviting. Go beyond green to create and maintain accessible nature rich spaces with more nature to engage with.

Encourage Environmental Action Through Connection

- Promote campaigns that strengthen nature connectedness to drive conservation behaviours, especially among infrequent nature visitors. The research shows that connection significantly boosts environmental action even without frequent visits.

Leverage the synergistic effects of nature visits and connection

- Encourage frequent nature visits while simultaneously fostering a deeper emotional connection to nature.

These policies are relatively low-cost, scalable, and address both mental health and environmental issues by leveraging the compensatory and synergistic effects of nature exposure and connectedness.

Final thoughts

Previous research has tended to focus on nature exposures, nature connection and key outcomes of wellbeing and environmentalism in isolation. The present work unites these aspects, supporting previous results found in isolation, but importantly demonstrating the compensatory and synergistic relationships at play.

These findings offer a roadmap for tackling mental health and environmental crises together. By understanding how nature visits and connectedness interact, we can design smarter interventions that maximize benefits for people and the planet. It’s a reminder that our relationship with nature is complex, but full of potential.